A staggering number of older adults globally, nearly 24%, are living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition often seen as a precursor to dementia. This is according to a new report analyzing over 50 studies, highlighting the critical need for improved diagnostic strategies and interventions.

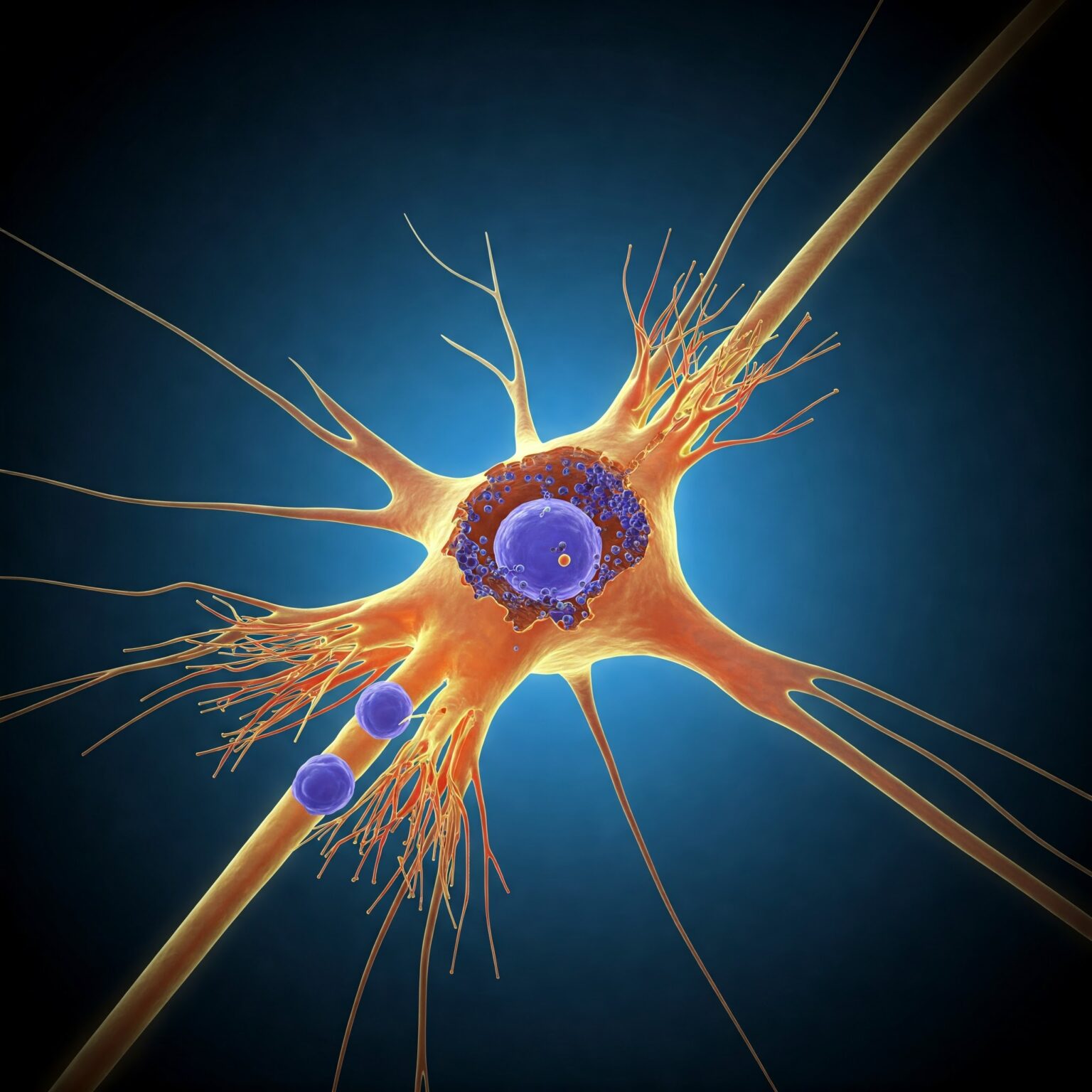

MCI, characterized by early-stage memory loss or decline in other cognitive abilities, subtly impacts daily life but can significantly affect an individual’s overall well-being. While it’s not dementia, the report published in BMC Geriatrics underscores its progressive nature. Researchers pinpointed age, educational attainment, and depression as key factors influencing MCI in older populations. Notably, the prevalence of MCI climbs sharply with age, and factors like depression and a BMI over 30 appear to elevate the risk for those between 50 and 64. The authors suggest that age-related brain changes, such as atrophy and neuronal fragility, contribute to this increased risk.

The situation in the United States appears particularly concerning. Alarmingly, two separate reports from last year indicate that over 7 million Americans may have MCI without a formal diagnosis. One study revealed that less than 8% of MCI cases were accurately identified in the four years leading up to the pandemic. Out of the estimated 8 million individuals expected to develop MCI, a shocking 7.4 million remained undiagnosed. A second study focusing on primary care clinicians found that a staggering 99% were underdiagnosing the condition.

This widespread underdiagnosis presents significant challenges for the nursing home industry. Early identification of MCI can allow for timely interventions and support, potentially slowing the progression to dementia and improving the quality of life for residents.

“Early detection of mild cognitive impairment is crucial,” says Dr. Eleanor Vance, a leading geriatrician not involved in the report. “It allows us to implement strategies focused on cognitive stimulation, lifestyle adjustments, and managing co-existing conditions like depression, which can make a real difference in the trajectory of the condition.”

The implications for nursing homes are clear. Recognizing the prevalence of undiagnosed MCI within their prospective and current resident populations is paramount. Implementing robust screening protocols and staff training to identify early signs of cognitive decline can lead to more person-centered care plans and better outcomes. Furthermore, understanding the risk factors associated with MCI can inform proactive strategies to support residents’ cognitive health.

As the aging population continues to grow, addressing the silent epidemic of undiagnosed MCI will be increasingly vital for the skilled care sector. Failing to recognize and manage this condition not only impacts the individuals affected but also places a greater burden on nursing homes and the healthcare system as a whole.